Last week, after spotting that Norlis Antikvariat had just released their spring catalogue, I took a lunchtime trip from the office over to the bookshop to pick up a copy and to have a wander among their shelves.

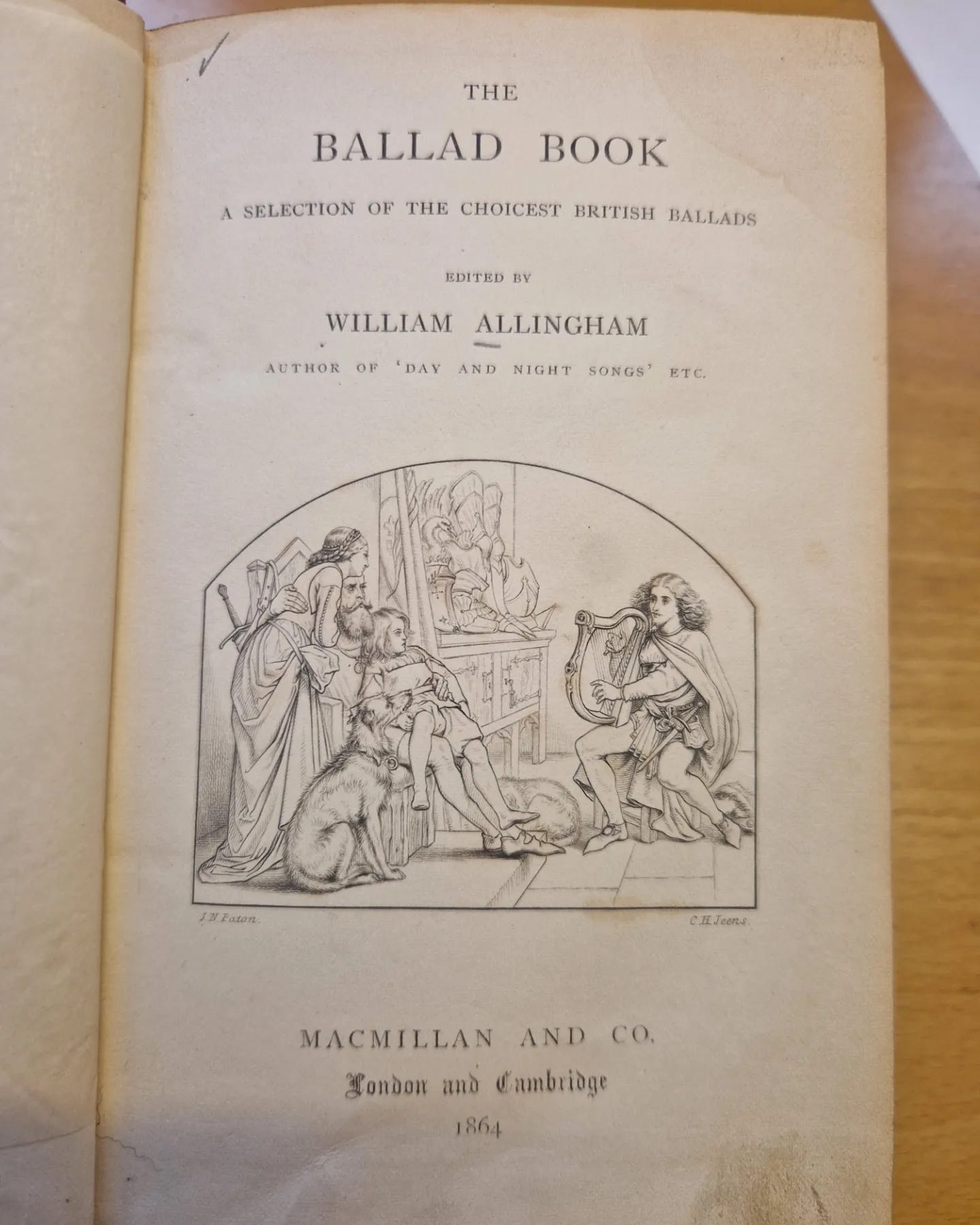

I went up to the second floor and in the room with fiction, where a selection of English language books are kept, I browsed quite idly until I saw a fairly suntanned spine on which were the words The Ballad Book. My persistent interest in ballads and the history of ballads made me curious.

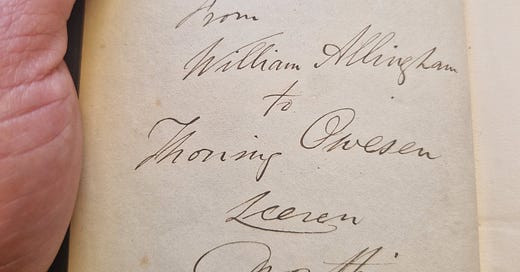

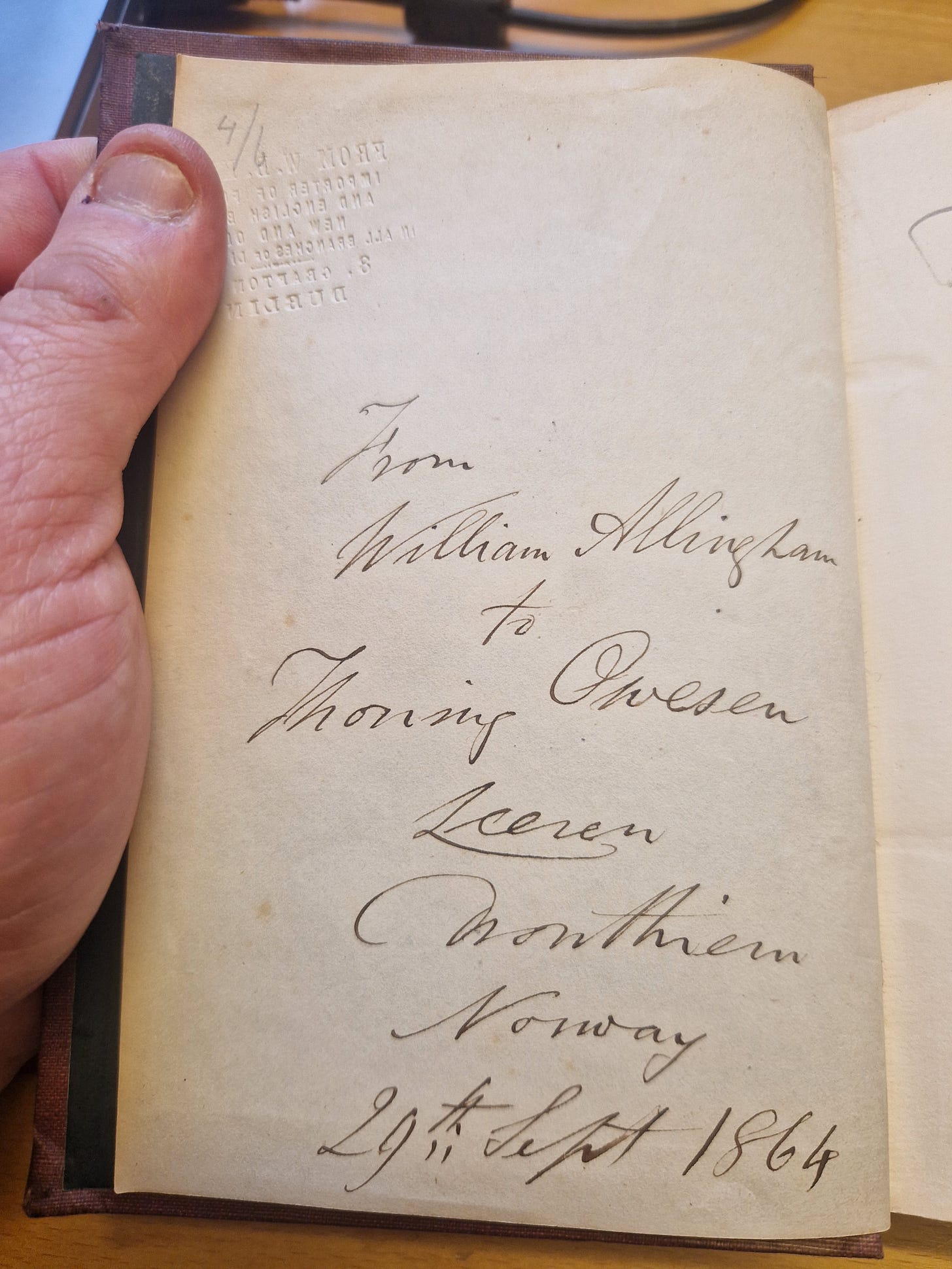

The book fell open on a page with a dedication:

From William Allingham

to Thoning Owesen

Leren

Trontheim Norway

29th September 1864

I recognised the names immediately, and tentatively checked the insert with the books description and price. 300 NOK, about €30.

William Allingham, an Irish poet whose reputation has faded with time, but who influenced Yeats and John Hewitt, was a relation of Thoning Owesen, who had grown up largely in Ireland. William was the nephew of Jane Allingham, Thoning Owesen’s mother who had married successful Norwegian merchant Otto Owesen.

Owesen was born in Dublin, living in a family home named “Ballyshannon” in Trondheim until his mother’s death when he was three years old. Following this, he was sent back to Ireland and raised among grandparents and various aunts and uncles and educated at Foyle School in Derry. During this period, his father also died when Thoning was just eight. When he finished his schooling, he returned to Trondheim to tend the family fortune which he now inherited and he would spend the majority of his life in Trondheim at the farm he purchased “Leren”, where William dedicated a copy of the new book he had just edited to his relative.

The farm was a large one, and included saw mills. Owesen seems to have been something of an enlightened if paternalistic owner-employer, holding an annual christmas eve dinner for his workers and giving all of them a gift annually. He was apparently also noted for his punctual payment of wages.

According to several short biographical notes, Owesen underwent something of a personal crisis of faith and began to give serious consideration to his fortune after his death. He never married nor had children. Among the things his fortune was set aside for at his death in 1881 was the establishment of Dalen school for the blind, the first of its kind in Norway, and for many years the only such institution in the country.

I first became aware of Owesen and his story last summer when on a visit to Nidaros cathedral in Trondheim I came across his headstone by accident, the word DUBLIN on his headstone standing out a mile in a see of 19th century Norwegian headstones.

To find this book then was total serendipity for me, though the book’s dedication is not the only story it reveals. In addition to Allingham’s dedication to Owesen, three other names are found on the book.

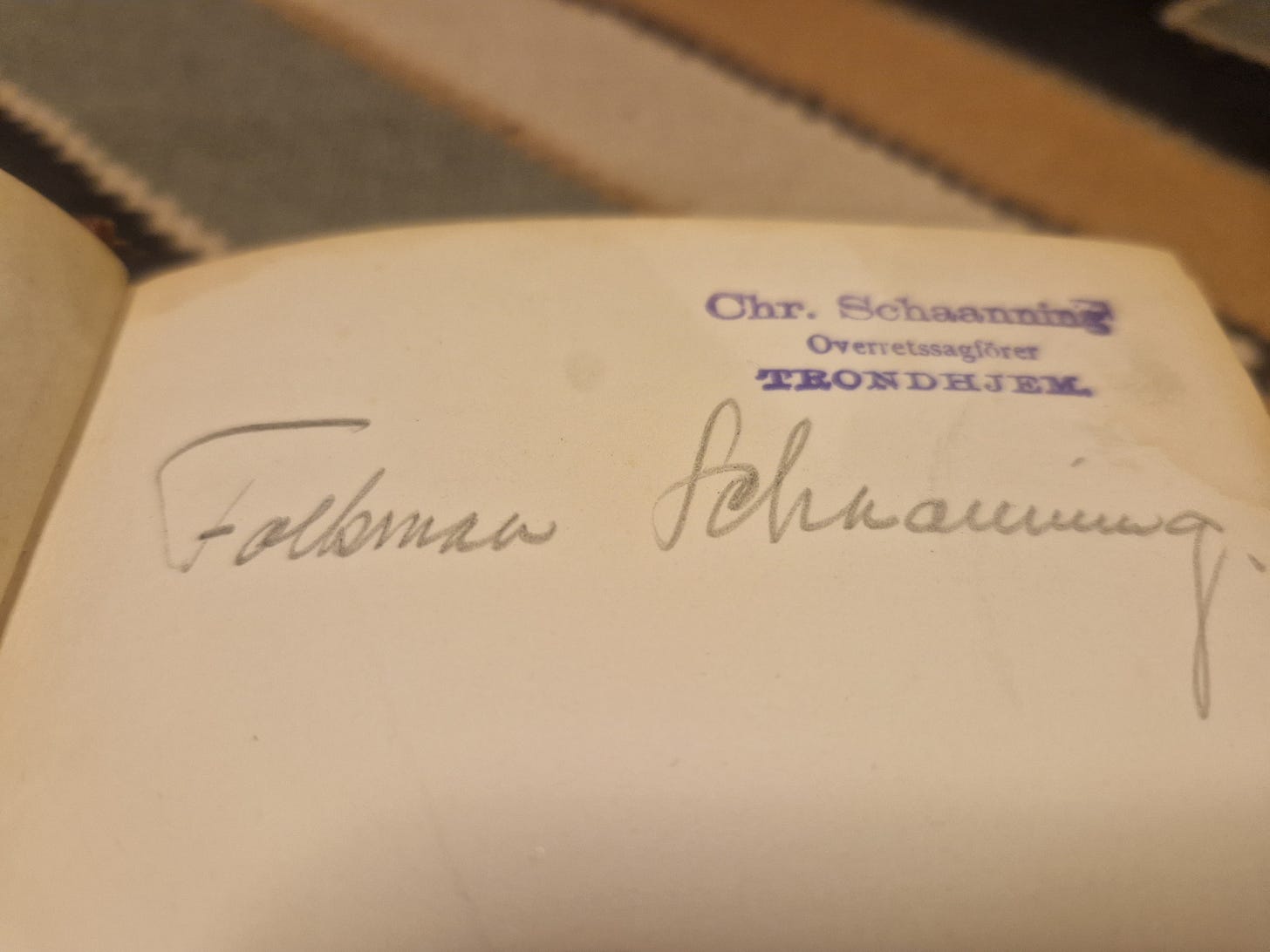

In pencil, there is the unusual name of Folkman Schaanning, and on the same page a stamp with “Chr. Schaanning Overrettsagfører Trondhjem”. Christian Knudzton Schaanning was a jurist and city councillor in Trondheim from a well-to-do family and was mayor of Trondheim in 1985 and 1986. The second name on the same page, the one in pencil, belonged to Christian’s son Folkman who was an actor and early film actor in Norway, appearing in films between 1934 and 1954 including a 1948 French-Norwegian production that told the history of the heavy water sabotage at Rjukan during the Second World War, a story that later was made into The Heroes of Telemark starring among others Richard Harris and Kirk Douglas.

The final name on the book comes from an ex libris card on the inside of the cover, Hedvig Schaanning likely Christian Schaanning’s daughter.

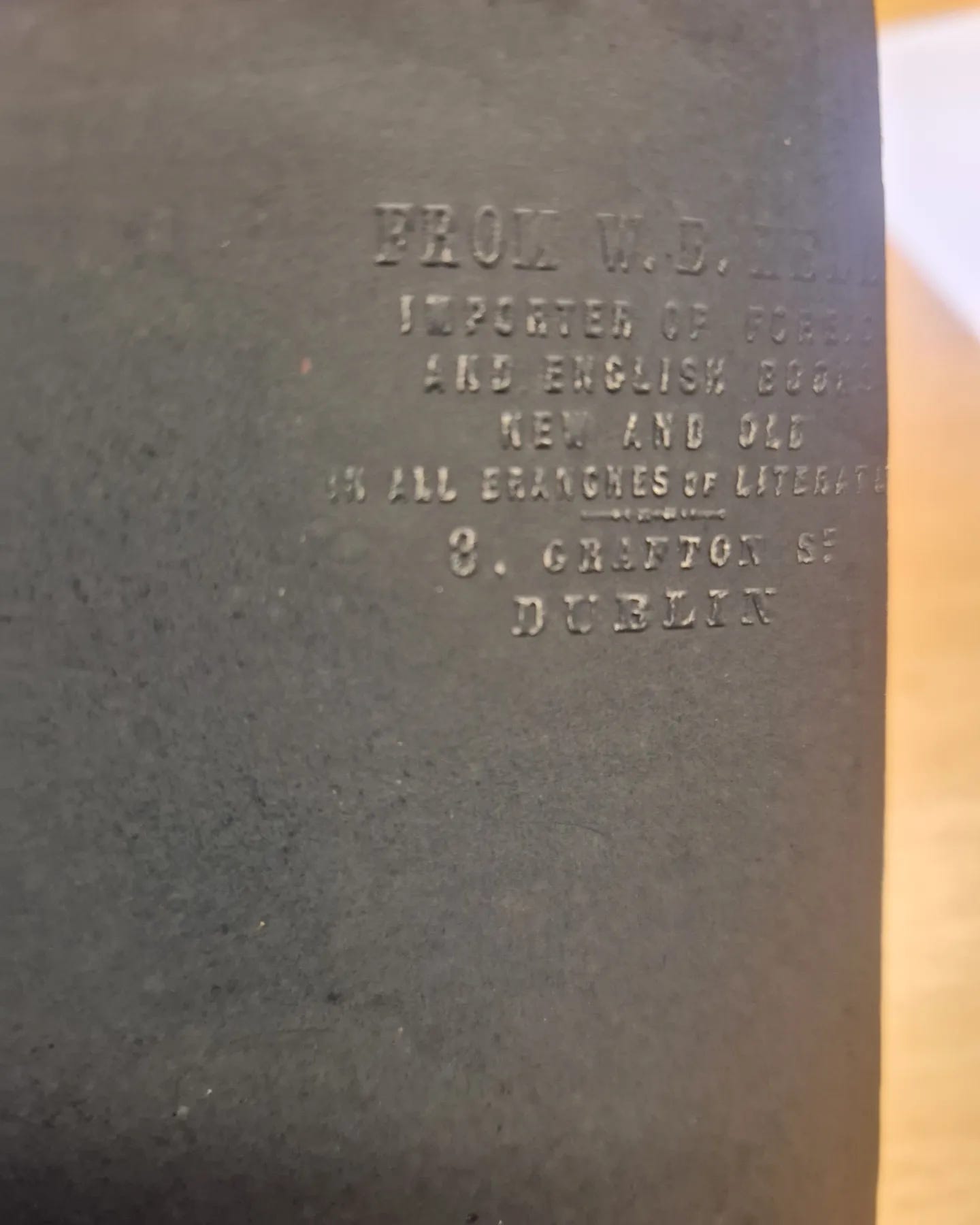

Another name actually does appear on the book, one that is cut off slightly but is an embossed stamp that reads:

FROM W.B. KELLY

Importer Of Foreign

And English Books

New And Old

In All Branches of Literature

8 Grafton St.

DUBLIN

So far, I haven’t happened upon much about them, so any information would be gratefull received.

Before leaving off this little diversion, I should say that the actual contents of Allingham’s book are in and of themself interesting with his interesting introduction to the collection of ballads, although a discussion of his actual attitude to ballads, ballad collecting, “corruption” of texts, and other opinions on what constitutes ballads worthy of collection is for another day or another forum.

Still, it can be said in a fairly general way that his interest in ballads, and doubtless his interest in the northern reaches of Europe through his relation Thoning Owesen are evident in his relating of the following (presumably apocryphal) story:

In 1586, Sophia, Queen of Denmark, visiting Tycho Brahe, prince of stars, in his island-observatory, was there storm-sted three days; when to amuse Her Majesty a store of old Danish Ballads, collected by Pastor Sæffrensen, a friend of Tycho’s, was produced; and, with the Queen’s encouragement, a selected hundred of them were published in 1591, under the title of Kæmpe Viser, Heroic Ballads.

He goes on to say that “Among the Scandinavian ballads are found parallel stories” to our own. Allingham writes that “This strong family likeness to old foreign ballads is in itself no bad evidence for the antiquity of ours.” Indeed, as a recent book published in Norway, Skillingsvisene i Norge 1550-1950: Studier i en forsømt kulturarv there is at least one chapter that shows the spread of a broadside ballad in print about a knight named Brynning throughout the Scandinavian region from 1701 right to 1901. That ballads would find their way beyond these confines and into other languages like German or English should be of no surprise to us whatsoever. As Anne Sigrid Refsum rightly notes in her conclusion to her chapter, “the feelings that are depicted in [Brynning] remain recognisable across time and the conventions of love, even today.” The same can be said of many of the ballads to be found in Allingham's collection, some of which have received many modern treatments.

On The Bookwheel

William Allingham, The Ballad Book, MacMillan and Co., 1864.

Brandtzæg, Siv Gøril and Strand, Karin, Skillingsvisene i Norge 1550-1950: Studier i en forsømt kulturarv, Scandinavian Academic Press, 2021.