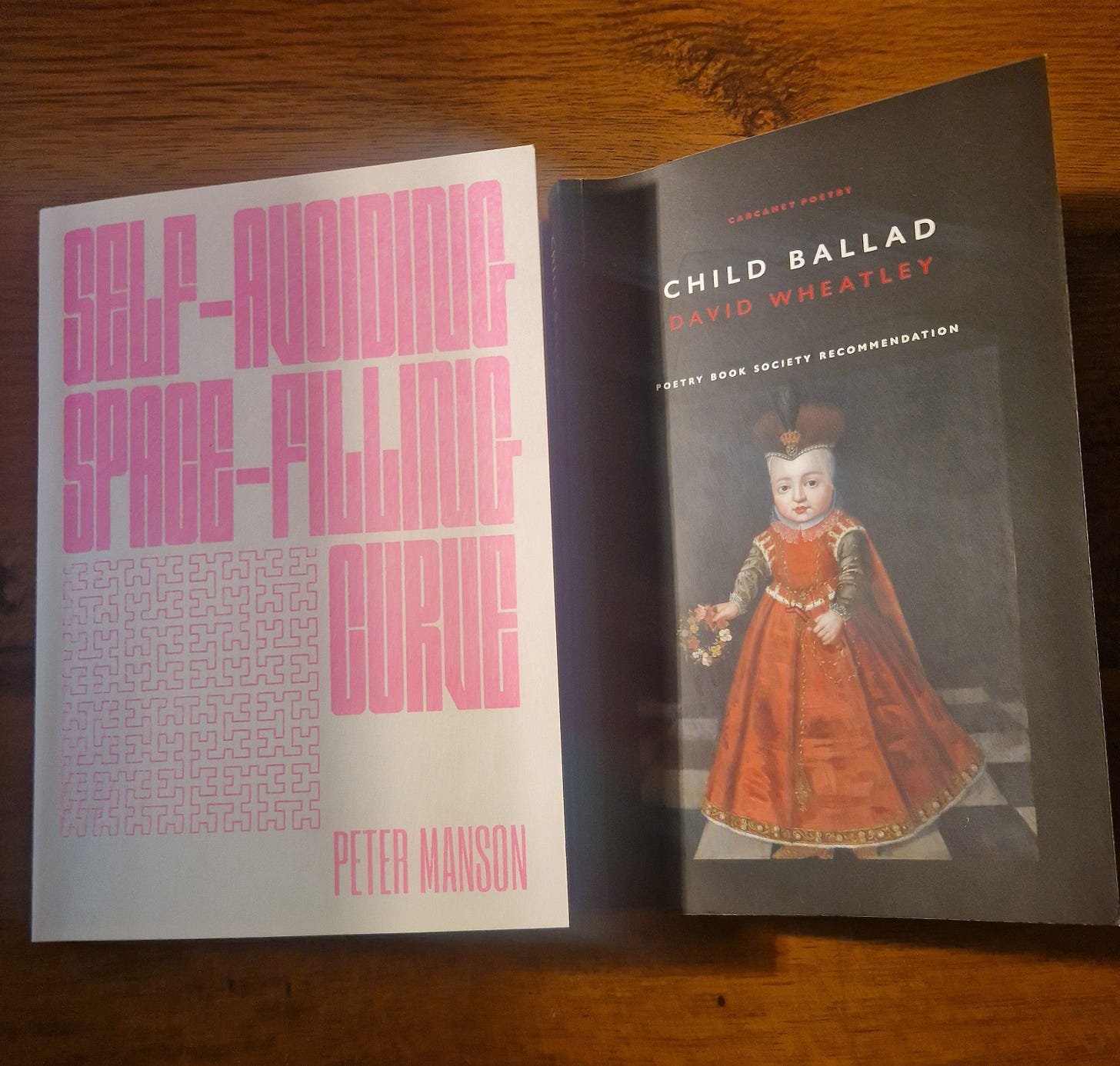

Two new poetry books recently arrived to me here in Norway that I’ve been looking forward to for a while: David Wheatley’s new collection Child Ballad published by Carcanet and a new chapbook by Peter Manson, Self-Avoiding Space-Filling Curve from Just Not Press.

There are undoubted affinities to be found in the writing of Wheatley and Manson, and that feels especially the case on this occasion, the least of which being that both are resident in Scotland. More pertinent is their approach to assembling their poems from a wide range of disparate sources.

The title of Wheatley’s new collection plays on the term often used to refer to the ballads of England and Scotland collected and edited by Francis J. Child in the later 19th Century. Such ballads are often referred to as being Child Ballad number 23 or whatever the case may be based on Child’s organisation of the ballads in his The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. This system of reference is now often done alongside the reference to a ballad’s Roud number, a system devised by Steve Roud.

Wheatley’s collection then indicates a certain engagement with the ballad tradition in the poems, but the Child part of the title relates more to Wheatley’s experience of becoming a father than any direct reference to Francis J. Child as such, although as always in Wheatley’s writing there are rich veins of crosshatching from Irish and Scottish traditions in his work, as in “Adomnan’s Sermon to the Oil Rigs” to take just one example:

I saw the sandstorm coming and built my chapel

on sand. I would number the oil-fields named for saints

and seabirds: Ninian, Columba, Shearwater,

Auk. Sea-spray and thunder; kittiwake’s egg

of a scarred moon. I sense Ninian’s faint candle

out in the North Sea and the gannet scissoring up

Recently, I have just finished reading The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper, and have been more generally interested in the history of how books were written in the early modern period. The importance of extracting, and what is often known as compiling commonplace books of quotes, ideas, thoughts was a central method of assembling notes towards writing of books throughout the period in which paper became more readily available in Europe was a vital part of shaping a text from other texts. Peter Manson’s poetry, especially in Self-Avoiding Space-Filling Curve feels very much a part of this tradition, while also in his inimitable way, with his exceptionally well-tuned ear for mutated meaning in words. In some respects, it reminds me of his much larger work Adjunct: An Undigest.

Like the old ballads—on which several of these poems draw—the real skill displayed by Peter Manson in these poems is in the weaving together of these different sources. This is not mere excerpting or cut-up technique but something more sophisticated and subtle.

The cuckoo verses not only of Child Ballads are being used here but the phrasing of Wikipedia articles, as well as contemporary song lyrics, and even the long lives of poetic paraphrase.

Take for instance the poem “lines composed a few feet below tintern abbey”, which riffs very clearly on one of Wordsworth’s best known poems:

i saw a ship in site-specific immolation

of young iambs bound by a code of honour revoked

to save my sorry gammon pig thinks of a colour

the sty turns blue in the birth canal as the party

becomes uninhabitable 0 deaths in scotland

my named and memorable acts of brutality

forgotten by me alone as the head engages

the dust here is nine tenths shit in the abbey tunnel

old parts alight with a phosphorescent jaw for war

as if we can’t have both these wipers inside a pig

things heard on the brink of the sleep of reason inbred

to outsource self-awareness to the unknowing cloud

of discontinuous starlings under all bright stars

That final line in particular as I read had a strange resonance to it, and sure enough when I checked the notes providing the sources for each of the poems (online here) Peter writes in clarification of this line:

“the unknowing cloud / of discontinuous starlings under all bright stars”, The Cloude of Unknowyng, an anonymous 14th Century work of English mysticism; also Wordsworth, “The Daffodils”: “Continuous as the stars that shine / And twinkle on the milky way”; Also John Keats, “Bright star, would I were as steadfast as thou art”.

Here then the stars stretch across the temporal plane, as stars do when sending their light, from the original quote taken from 14th century English mysticism through Wordsworth and Keats to us now in this new version of an old song, thanks to Peter Manson. That rich density of allusion is the hallmark of these poems.

In taking so many threads and leaving us with single unified poems, Manson in a curious way is also part of that tradition of ballad-collecting that from many versions makes one. As a final example, the poem “willy’s lyke-wake”, plays on several Scottish ballads including the “Lyke-wake Dirge” (as an aside: a lyke is a corpse, and the modern Norwegian word for corpse is also lik), as well as “The Jolly Goshawk” and more:

i bought a soap dish that smells of condom lubricant

with a hey the cuddie o’er the kye et cetera

and in that soap dish there was literally nothing

…

o bury my body in sussex my bi goshawk

to bequeath unheated in its original box…

Incidentally, Peter Manson will be reading from this new book of his in University College, Cork in Ireland along with Trevor Joyce and Randolph Healy in a few days’ time. All three are launching their respective new books: Peter Self-Avoiding Space-Filling Curve, Randolph his first book of poems to be published in the USA The Electron-Ghost Casino while Trevor will be launching Conspiracy out now from Veer. It takes place at UCC Library on Thursday, 22nd February from 5.15pm.

The event is also to mark the accession to UCC library of the Soundeye Archive. I wrote an oral history of the Soundeye festival which ran from 1997—2017 in The Stinging Fly in 2022, which you can get here. It’s great to see that the documentary archive related to this important festival of poetry which took place for twenty years in the city of Cork now has a home in the university library there. Hopefully it will prove a fruitful repository for future researchers of the unique nexus that Soundeye represented in its 20-year history and its continued afterlives.