There was a display of the Northern Lights above our house on Thursday night which we stood out and watched in the damp grass of the garden at about 10.30pm. My phone was dead so Miriam took some photos. Its the second time in just a few weeks that we have been able to see the lights strongly from our own front door. The last time was just two weeks ago on 30 August.

The Northern Lights are very difficult to see with the naked eye, and are never as brilliant to the eye as they are through a lens. Since the relatively early days of photography, attempts have been made to capture the Northern Lights, right back into the nineteenth century.

After the recent displays here locally to me, I have been looking through DigitaltMuseum, the online repository of digitised objects, photographs etc. from around Norway’s museum collections and have been captivated by several of the early images that were taken to capture the northern lights.

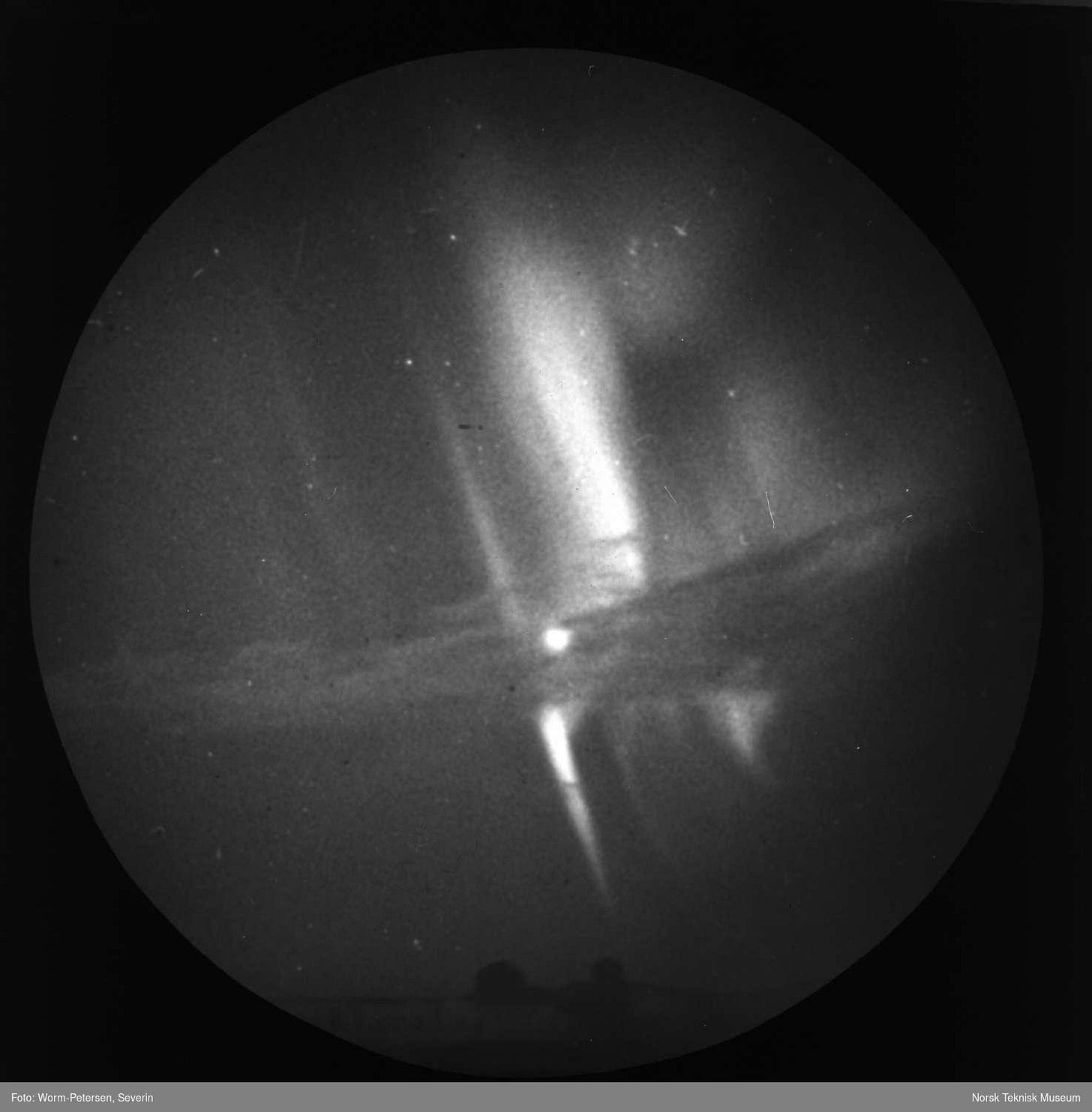

I have become especially interested in the work of two men: Severin Worm-Petersen and Fredrik Carl Størmer. Both men have left behind remarkable archives of their photography efforts, and the photos of the Northern Lights they took are especially affecting to look at. There is something about seeing the images produced on early photographic equipment, without colour, that captures just as well the sheer eeriness of seeing the Northern Lights. Looking at the photos taken by Worm-Petersen and Størmer, both taking photos in northern Norway in a place called Bossekop, the absolutely cosmic quality of the Northern Lights is captured even if they do not capture—as our phones so easily do today—the colourful display of the Northern Lights.

Severin Worm-Petersen was a studio photographer based in the centre of Oslo, called Christiania for much of his life, who moved his studio quite a bit but who became known as a portraitist but also as a daring photographer en plein air making him a sought after photographer of major public events and sporting occasions. Among his famous interior photographs of current affairs is the oath read by King Haakon VII on in the Norwegian parliament in 1905 when the union with Sweden was ended.

Capturing dynamic events was something Worm-Petersen had likely learned while trying to capture the dynamism of the Northern Lights.

Worm-Petersen’s enormous archive of negatives—some 30,000—became part of the collection of the Norsk Teknisk Museum after his death in the 1930s.

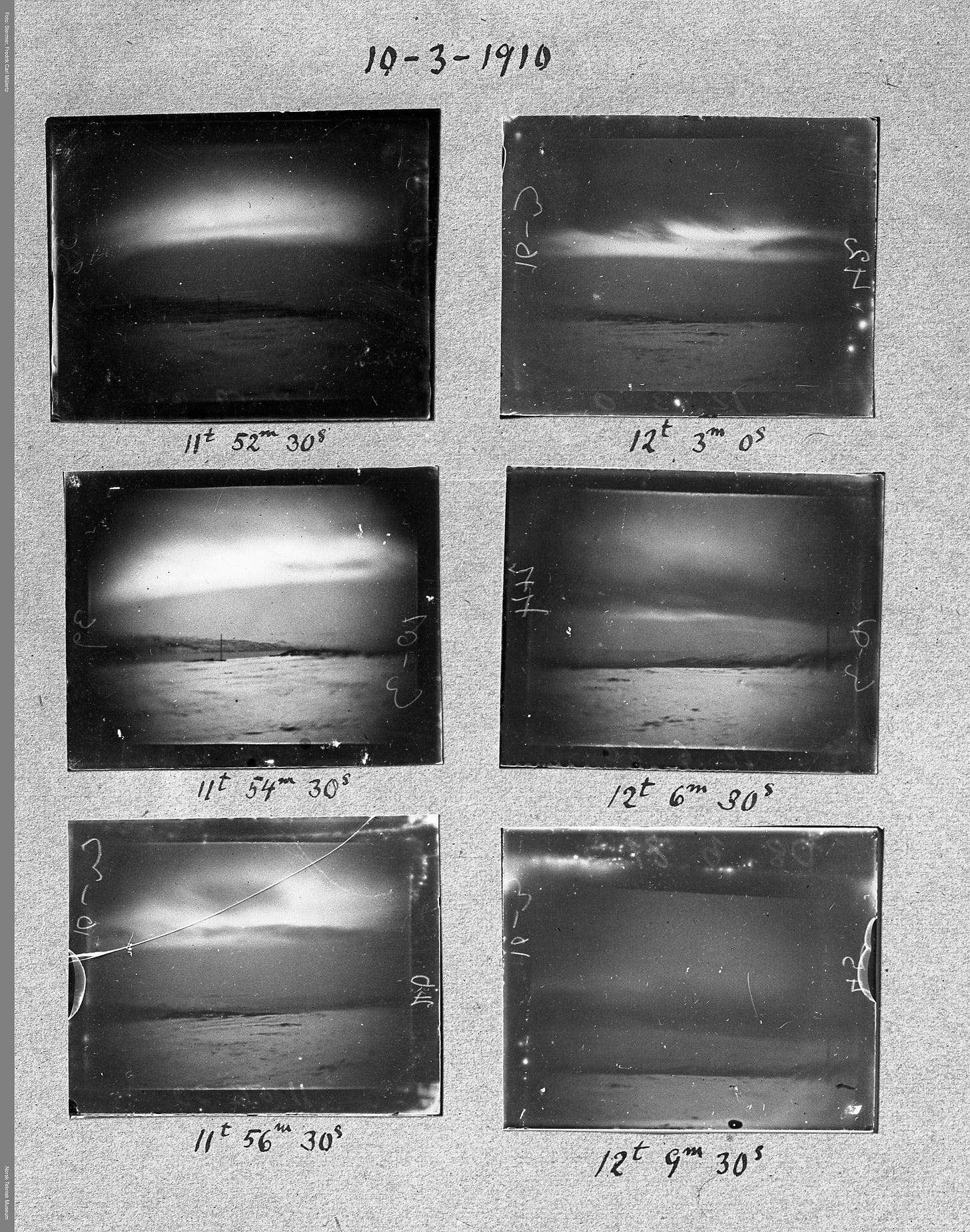

At the same time as Worm-Petersen was working, so too was Carl Størmer. Carl Størmer, from Skien in Telemark—home also to Henrik Ibsen—was obsessed with the Northern Lights. A mathematician, he developed mathematical tools to calculate the paths of electric particles around a magnetic sphere. From 1909 he began a systematic experiment by photographing the aurora, and together with O. A. Krogness developed a special camera for aurora photography. He described and systematized the different aurora forms and went on to publish a photographic aurora atlas. Størmer also developed a method for determining the height of the aurora from simultaneous photographs from two different stations. These were the first reliable height determinations of the Northern Lights, and Størmer's further work on this, where he and his colleagues processed more than 14,000 observations, provided very accurate information on the height distribution of different types of aurora borealis. The results of his work were later summarized in The Polar Aurora (1955).

Størmer took many images of the Northern Lights and often had them developed by Worm-Petersen, like this series of photographs from 1910:

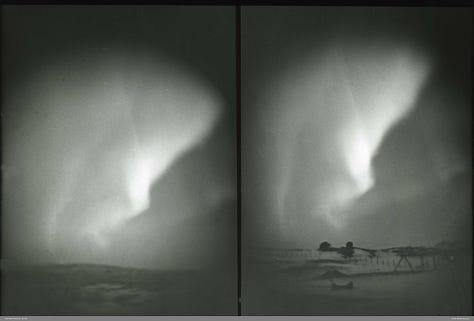

Many of the images were taken through two lenses, like those in this image below take by Størmer but produced in his studio in Christiania by Worm-Petersen, reminding me of the stereoscopes of that period.

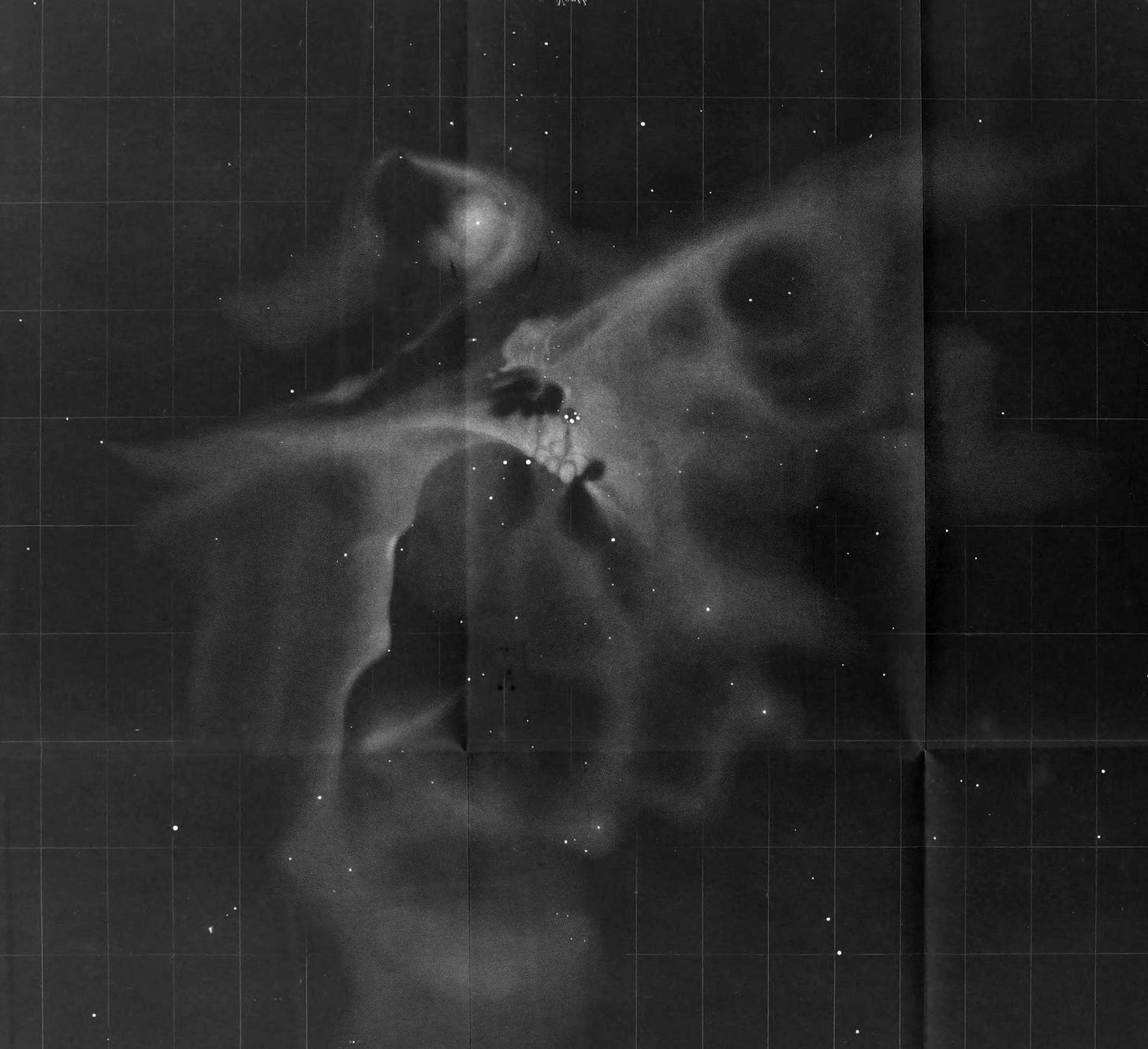

There are hundreds of images from Worm-Petersen and Strømer that can be found over their years of collaboration. To look at these images from around one hundred years ago, capturing a phenomenon whose recorded history dates back to the 10th century BC in China, is as spine-tingling to me as standing in my own garden and looking at the same phenomenon. There is something about the fact that Worm-Petersen, with his knowledge of how to capture live events, coupled with Størmer’s scientific doggedness in recording the phenomenon, that puts me in mind of figures Christiaan Huygens, or William and Caroline Herschel. One image from the work carried out by Worm-Petersen in developing images for Størmer, below, also reminded me of something else.

In his book Affinities, Brian Dillon writes about an image drawn by astronomer John Herschel (son of William, above) of the Orion Nebula, and how this drawing inspired Thomas De Quincey.

Although nebula observed through a telescope and then drawn are quite different to photographs from glass plates, yet I cannot help but feel a certain affinity between the images, and the rapturous writing it inspired in De Quincey in his essay “System of the Heavens as Revealed by Lord Rosse’s Telescopes” (1846) where he writes that:

What is it then that Lord Rosse has accomplished? If a man were aiming at dazzling by effects of rhetoric, he might reply: He has accomplished that which once the condition of the telescope not only refused its permission to hope for, but expressly bade man to despair of. What is it that Lord Rosse has revealed? Answer: he has revealed more by far than he found. The theatre to which he has introduced us, is immeasurably beyond the old one which he found… Great is the mystery of Space, greater is the mystery of Time; either mystery grows upon man, as man himself grows; and either seems to be a function of the godlike which is in man. In reality the depths and the heights which are in man, the depths by which he searches, the heights by which he aspires, are but projected and made objective externally in the three dimensions of space which are outside of him. He trembles at the abyss into which his bodily eyes look down, or look up; not knowing that abyss to be, not always consciously suspecting it to be, but by an instinct written in his prophetic heart feeling it to be, boding it to be, fearing it to be, and sometimes hoping it to be, the mirror to a mightier abyss that will one day be expanded in himself.

This is the sense I get when looking at the images created by Worm-Petersen and Størmer. Many eyes have looked at the heavens, and many eyes have seen the Northern Lights, but like Herschel’s drawing, the photography of Worm-Petersen and Størmer, and their systematic efforts to try and capture and understand the astonishing phenomenon that I saw in the shade of a tree in my own garden the other night, has a special kind of revelation to it. It is easy to imagine the excitement they felt when seeing the images develop in the studio of Worm-Petersen. As De Quincey asked of God in his 1846 essay:

of what is he the revealer? Not surely of those things which he has enabled man to reveal for himself, and which he has commanded him so to reveal, but of those things which, were it not through special light from heaven, must eternally remain sealed up in the inaccessible darkness.

Fascinating. Enjoyed this. I hope to be able to actually see the Northern Lights one day soon.