2024 has been a strange, dark year. Personally, a very fulfilling one: I had paid time off dedicated solely to writing, a Maddock Fellowship at Marsh’s Library in Dublin, and the news that I am going to be a father. Yet, the state of the world seems more hopeless than usual. Wars, climate breakdown, and the increasing rightward turn in so many countries all make for a particularly grim prognosis of the future.

Our baby is due on a fairly auspicious date: 21 December, the shortest day of the year, or the longest if you prefer. It is a day that has always been fascinating to me, all the more so since moving to Norway where it seems a day filled with extra meaning when the days are as short as it is possible to imagine.

Historically, the shortest day of the year was celebrated on the 12th December going into the 13th December, in the pre-Christian era and after. In Norway, Lussi was a folkloric figure, a supernatural female character who was loose on the night of the 12th, lussi Langnatt, and ensured that houses were well on their way to finishing preparations ahead of Christmas. All work that involved circular movements, such as spinning, grinding and using a rolling pin, was to be done by then. The circularity no doubt linked to the idea that this was the date when the shortest day happened, and so the sun was due to turn.

In Ryfylke, legend has it that Lussi caused a housewife who was rolling out lefse ( a type of flat potato bread) to go lame in her hand. In another story, Lussi caused a woman who had not finished her baking before Lussinatta to lose her hand. Other legends go that if she discovered a dirty barn, she threw dirt into the porridge that people ate.

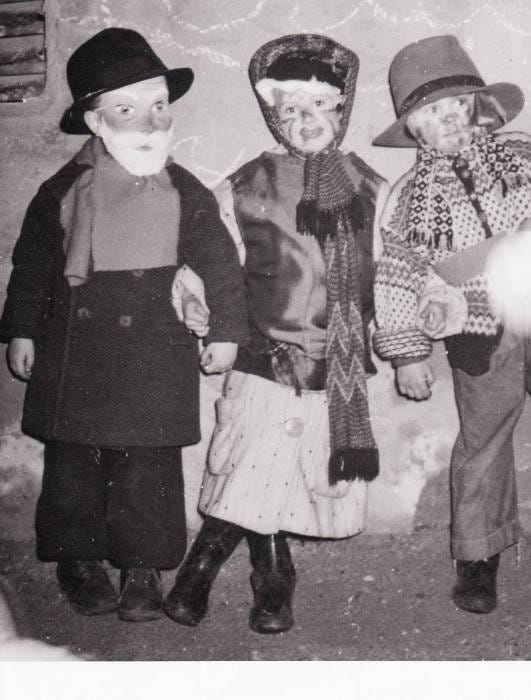

In some parts of Norway, “going Lossi”, is a tradition of dress-up and merry-making that strikes me as having a strong resemblance to Wren Boys in Ireland, which I’ll try to come back to later on, below.

St. Lucia is also celebrated on the 13th December, to remember a Christian martyr of the 4th century. St. Lucia is an especially strong tradition in Sweden, and to a lesser extent—and mainly among children—in Norway. One of John Donne’s most famous poems is “A Nocturnal upon St. Lucia’s Day”, which begins:

'Tis the year's midnight, and it is the day's,

Lucy's, who scarce seven hours herself unmasks;

The sun is spent, and now his flasks

Send forth light squibs, no constant rays;

The world's whole sap is sunk;

The general balm th' hydroptic earth hath drunk,

Whither, as to the bed's feet, life is shrunk,

Dead and interr'd; yet all these seem to laugh,

Compar'd with me, who am their epitaph.

So what has all this to do with the prospect of becoming a father? Well very little and a lot, I think. As a reader, one of the first things I did when I realised I was going to become a dad was to look at reading some books about it: there are practical guides to pregnancy for men, and the various stages, which have proved very useful. There are also more general books about the changing role of fathers in Western societies and how to approach that, which I have also read in the past few months.

But I wanted something else too, something about what it means to be a dad in what can often feel a rather hopeless age. A good friend recommended to me Infinitely Full of Hope, a work of philosophy about becoming a father in the era of late capitalism with all of its horrors and frustrations.

It was a vital thing to read. There seems so many reasons not to have children, and many legitimate reasons not to. The fertility rate in Norway is extremely low and is a cause for serious concern. Even in a country lauded for its excellent system of public healthcare for pregnant women, and the generous system of parental leave, subsidised kindergartens, there is no question that having a child is extremely expensive and that the children’s allowance paid out is paltry, verging on the insulting. And yet. Here we are about to have a child.

There’s no guarantee (in fact it seems unlikely) that our child will be born on her due date of 21 December. But the poet in me hopes that they are. Regardless, they will come into the world at a very dark time: seasonally and socially and politically. They will nonetheless be a little light, a light for us and for others in time.

On that note, and with Christmas and the due date fast approaching, I am thinking very much then about light and dark, and also the radical potential that Christmas and midwinter represent, of a different possible future. That was something I tried to articulate two years ago on here in this piece:

#24 - On Christmas

As we approach Christmas season, and the darkest point of the year, my thoughts are turning towards the ever vexed question of the “meaning” of Christmas.

Christmas, and the midwinter along with it, are ironically times of great renewal, a time infinitely full of hope. That seems more important than ever this year. Christmas is a time that has inspired some great art and I am especially fond of great writing and great music about Christmas. The occasion demands it. As Milton’s “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity” has it:

Say Heav'nly Muse, shall not thy sacred vein

Afford a present to the Infant God?

Hast thou no verse, no hymn, or solemn strain,

To welcome him to this his new abode,

Now while the heav'n, by the Sun's team untrod,

Hath took no print of the approaching light,

And all the spangled host keep watch in squadrons bright?

In that spirit, here are a few of my favourite pieces of music inspired by the season, and that have been earworms of mine for quite some time.

I mentioned above that “going Lossi” as practiced in Norwegian folkloric tradition bore striking similarities to the Wren Boys of Ireland, who go “hunting the Wren” on St. Stephen’s Day (26 December) in costume each year. Consider for a moment the image used above as the cover for Lisa O’Neill’s recording of the Wren Boy song “The Wren, The Wren.”

Here’s that image taken from the UCD National Folklore Collection taken in Athea, Co. Limerick in 1947 and a photo of some children around 1970 in Dalane in Norway “going Lossi”:

In terms of some reading for Christmas, I find it a time especially good for returning to tried and tested favourites, although what these are is continually added to. I have a steadily building collection of books around the theme of Christmas and midwinter. Last year, I got the rather nice Penguin Book of Christmas Stories which not unlike The Faber Book of Christmas has a good cross-section of stories about the season and its discontents as well as its joys.

I have become a habitual re-reader of “The Dead” by James Joyce each Christmas, as well as a habitual rewatcher of John Huston’s wonderful film adaptation from 1987 (and I believe his last film), which you can find on YouTube, and possibly elsewhere too. Christmas in our house now also always mean the new Winter Papers anthology, which is celebrating 10 years this year!

Two books which I recently read, in greedy anticipation of the oncoming Christmas season, was Ian Sansom’s December Stories I and December Stories II, which I was given as a gift by David of No Alibis Books in Belfast earlier in the year when their to take part in a panel with friends and fellow writers. The stories and characters, the irreverance and the reality of the pieces in both books have made them instant classics in my private canon of the great writing about Christmas. I strongly recommend getting your hands on them!

As we await our new arrival, and settling into life as new parents, I’d like to take a second to thank everyone who reads this—often all too intermittent—newsletter which I write. And while there will be a little hiatus for a few months, I will undoubtedly return at some point in your inboxes in 2025. In the meantime, wishing you God Jul, Nollaig Shona, Merry Christmas and all the best!