Since the birth of my daughter at the end of last month, a short nursery rhyme has lodged itself in my head and has become a go-to song these past few weeks when trying to settle her during late nights or days. It is incredible to think of what comes to you unbidden from the depths of memory during such life altering times. The rhyme as I sing it goes:

Haboo, ba-by bunting

Daddy’s gone a-hunting

Up the rocks

To catch a fox

And wrap the little baby bunting in

Haboo, ba-by bunting

On each repetition I rotate in different people so that Daddy, Mammy, our dog and even our daughter to whom I am singing, each get their turn in hunting the fox. This song is one I learned from my own mother, who I often heard singing it to my nieces and nephews when they were small, and in turn, I am sure it was sung to me and my siblings. I am fascinated by such songs and wonder how long the song has been in my family. Like all such rhymes and ballads, it seems to have quite an old provenance and a number of small but interesting variations.

Once I started to look it up, especially using it’s Roud Folks Song Index (11018 for anyone who cares to go down the rabbit hole) an immediate difference I noted from the version as I sing it to my daughter and those that are recorded in print is that the title and the first line is very often “Bye baby bunting” rather than the “haboo” I am used to. Growing up for me, “to go a haboo” was the most common word used around very small infants about going to sleep. Therefore it seems completely natural that in our family’s version of this song, we would start it with haboo rather than “bye”.

In the ever rich resource of the National Schools Collection of the Irish Folklore Commission, I find a version with an Irish language start from Fermoy Co. Cork:

Seo leo baby bunting

Dadda's gone a-hunting

Mamma's gone to milk the cow

to bring the baby something

The “seo leo” has a similar sound to the “haboo” we use while another similar version recorded in Lismore, Co. Waterford, which is near identical runs:

Cho hó baby Bunting

Daddy is gone a-hunting

He'll catch a hare

And skin it bare

To cover the baby Bunting

This is another difference between the version I grew up singing, and many of the version which I have subsequently found. Very often the animal to be skinned in older version is a hare, or a rabbit, rather than a fox.

A third version, in the main collection rather than the Schools’ Collection, from 1937 and collected in Leap, Co. Cork is closer to the one I am used to singing:

Hush-a-ba baby bunting

Dada is gone out hunting

to chase the fox across the rock

and bring back baby something

The hush-a-ba is close to the haboo and in this version, there is the fox and rock rhyme, although the order is reversed.

The hush-a-ba is close to the haboo and in this version, there is the fox and rock rhyme, although the order is reversed. Returning to the Schools’ Collection of the Irish Folklore Commission, I found – via the Roud Folk Song Index on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library – a version that has haboo, but spelled “Habu”, collected in Co. Clare:

Habu, baby buntainyour father is gone huntin

to catch a hare.

to skin a hare,

to make a cap for baby buntan

The rhyme seems to have originated in what is considered to be one of the key texts for English language nursery rhymes, Gammer Gurton's Garland: or, The Nursery Parnassus, compiled by Joseph Ritson and first published in 1783, where it appeared on page 36 as follows:

Bee baw bunting

Daddy’s gone a hunting,

To get a little lamb’s skin,

To lap his little baby in

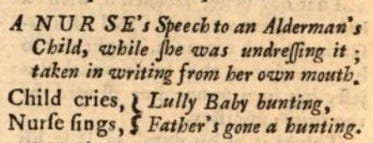

While inclusion in this significant volume no doubt was to see the rhyme spread itself across the anglophone world, it is not the oldest printed version I was able to find. IN The Gentlemen’s Magazine of April 1731, there is a brief mention of a version of the ballad in relation to a nurse who was supposedly the former wife of a butcher at Newport market.

The song has reached very far indeed in its time, even appearing in the recordings of Alan Lomax from his time in the Caribbean in the early 1960s. A very short recording of a version of the song recorded in August 1962 in Pembroke, Tobago can be heard here at the link. Lomax and his father before him, John Lomax, unsurprisingly also recorded versions of the rhyme in Kentucky and other parts of the United States.

Given that versions of this song stretch back at least three hundred years in print, it seems likely—as is nearly always the case with these things—that its roots are much older again and that it has been sung perhaps since sometime in the 17th century. One thing that strikes me is that like all folk songs, it is endlessly variable while at the same time retaining a core structure that changes little, even through variations in print, and being captured by folklorists.

The abiding strength of the rhyme, and the “narrative” captured within it, is also I think worth stopping and pausing to reflect on for a moment in terms of its longevity: coming as it does from a time when animal skins were something one hunted for and stripped oneself (although at least one version mentions going to market to get a skin), it indicates a desire on the part of the parent to provide material comfort as well as succour. That remains a universal desire of parents.

I wonder how common this rhyme is still, or has it survived as a strange relic in our family? I’d be very interested to hear from anyone familiar with it, or a version of it!

The motifs: a hunter father, a skin to clothe the baby, imitative syllables, all go back a very long way, to the Old Welsh 'Peis Dinogat', which was preserved as an interpolation to Y Gododdin, perhaps because it has an elegiac element - the father is referred to in the past tense. I'm always sceptical of claims of extreme antiquity for folklore, but it does demonstrate a continuity of mood, the contrast between but also interdependence of the hearth and the heath.

A lovely story! My mum used to sing me a bedtime song which went ‘Sleepy old Joe / Sleepy old Joe / Where does he go to / I don’t know / Does he go to [insert place/activity] tomorrow? / Yes yes yes / But now he stays here / At [insert current address]’. Her mum sang it to her and I’ve sung it to my kids. But I’ve never found any trace of a wider tradition i.e. my best guess is that my Nan made it up.